Rudy Augarten – avenging the Holocaust

Rudy Augarten in the cockpit of his P-47 Thunderbolt during World War 2.

Rudy Augarten was in his early 20s when he flew P-47 Thunderbolts for the US Airforce. On June 10, 1944, soon after D-Day, Augarten left from a base in southern England for a search-and-destroy patrol in a flight of four P-47. The sky was overcast, and the planes came down through the clouds over the French town of Caen. Below, a battle raged between the Germans and the Allies. Caen was well defended by the Germans, and anti-aircraft fire started to rock the planes. The pilots quickly pulled up to avoid the German flak. Suddenly, smoke began to fill the cockpit of Augarten’s P-47. He had been hit. "You’re on fire!" one of the other pilots radioed to Augarten. Augarten’s situation was critical. By now, the patrol had drifted further inland over German-occupied France, and Augarten needed to bail out. He opened the plane’s canopy and dove over the side. The bailout did not go smoothly. Augarten had forgotten to take off his oxygen mask, and it hit him in the face. As he plummeted toward the ground, he groped for his parachute cord. It took a few moments, but he finally found it and pulled. Augarten landed in back of a French farmhouse. As Augarten hit the ground, he had with him only the uniform on his back and an escape kit that contained some food and a little bit of money – but no gun. The farmer in whose field Augarten came down had seen the plane crash. The Frenchman ran out to give the pilot a pair of overalls, but, apparently fearing the Germans might come at any moment, quickly sent Augarten on his way. Augarten started walking and, after about a mile or so, came to another farmhouse. He knocked on the door, and a farmer answered. Augarten knew only a few phrases of French, and he used one then: "Je suis American" ("I’m an American"). The farmer and his wife decided to hide Rudy. But he stilt wasn’t safe. German troops came by the farmhouse regularly, and each time Augarten hid in the attic while they searched the area. After two weeks, Augarten felt he could no longer endanger his French hosts. He left early one evening and wandered through the countryside. He tried to work his way toward the front, hoping to sneak past the Germans and back to the American lines. As he walked, he was constantly on the lookout for German patrols. After hiking all night, he came upon another farmhouse, but this one looked strangely familiar. Augarten couldn’t believe it – he had walked in a giant circle, and was right back where he started. He stayed for another week, but grew increasingly concerned about the harm to his hosts if the Germans found him. Augarten was also desperate to get back into action. There were railroad tracks a few hundred yards from the farm, and this time he decided to follow the tracks toward the front line. After walking for a while, he came upon some Frenchmen, and again identified himself as an American GI. One of the men led Augarten to a ditch, where a group of British paratroopers who had been dropped off-course were already hiding. Augarten and the other soldiers stayed in the ditch for about a week. Each day, a Frenchman brought food. One day, however, he told the men he had seen Germans in the nearby fields. With danger so close by, he could not continue to help them. The men decided to break up into pairs and leave the area. Most decided to go to Spain, about five hundred miles away. But Rudy and one of the paratroopers decided to try to get through the front lines. Before going their separate ways, they divided up their weapons, and Augarten ended up with a pistol and a grenade. That first night, Augarten and his partner encountered a group of German soldiers. From a distance, one of the Germans called out in Augarten’s direction,"Sind sie das, Karl?" ("Is that you, Karl?"). There was no time to think. "Ja", Rudy answered the soldier, using his scant knowledge of German to maximum effect, and walked away. Apparently convinced that he was another member of their unit, the Germans did not follow. Augarten and the British paratrooper continued walking through the night. Several times they crept past German soldiers sleeping in foxholes, as the two moved closer and closer to the front. As day broke, however, their luck finally ran out. They were walking down a road bordered on both sides by hedgerows when Augarten saw a German soldier a short distance away. "Halt!" – the soldier shouted. "I’m going to give up," – whispered Rudy’s partner. Augarten had other plans. He threw the grenade at the German and then scurried behind one of the hedgerows on the side of the road, finding shelter in a ditch. All hell broke loose. The grenade exploded. The Germans began firing their machine guns wildly, raking the hedgerows. They were trying to get him to fire back and give away his position. Augarten kept still. The Germans stopped shooting and started to search the area. Finally, after about half an hour, they spotted him. This time, Augarten had no choice. He surrendered, and was taken prisoner along with the British paratrooper. Augarten was relieved to discover that the Germans who captured him were not from the SS. Like all Jewish servicemen in the American military, his dogtags identified his religious faith with the letter "H" for "Hebrew." Augarten knew that, as a Jew, he would not have had much hope of surviving capture by the SS. But Augarten’s captors were not interested in his religion or ethnic origin. They took him and the paratrooper to an abandoned brick factory, where two captured Canadian pilots were also being held. After three days, the prisoners were moved to a horse farm, which had been converted by the Germans to serve as a POW camp. The farm had a U-shaped building with nearly two dozen stables surrounding an open courtyard. In each stable, the Germans placed ten-to-fifteen Allied soldiers, separated by rank. Augarten, a second lieutenant, found himself in a stable with thirteen other officers. Each morning, the Germans lined up the prisoners in the courtyard and counted them. Afterward, Augarten and the others were free to wander in and out of the stables, and talk to other prisoners. Soon after arriving at the farmhouse, Augarten met Gerald Gordon, a British paratrooper. Gordon worked in the farmhouse kitchen making food for the prisoners. Several days after the two men first met, Gordon smuggled a knife from the kitchen back into the stables and gave it to Augarten’s group of officers. With the knife in their possession, the men began to discuss a possible escape attempt. Augarten wanted to go, as did Gordon, the two Canadian pilots from the brick factory, and two British officers. The rest decided to stay. A few nights later, the six escapees gathered in Augarten’s stall. Using the knife, they cut an opening in the stable’s soft wood ceiling. One by one, each man climbed through to the attic above. After a short search of the attic, they found a window. They realized their plans had not gone unnoticed. Someone, probably the wife of the stable owner, had left a large dish of butter by the window. None of the six had eaten butter for weeks. The two British officers quickly dug in with their bare hands. Augarten and the others grew impatient. They wanted to move on as quickly as possible. The British finally finished eating, and the men huddled around the window. Looking out, they spied a guard making a pass every quarter hour. The window was about fifteen feet above the ground, and the men knew they risked injury if they tried jumping. Moving quickly, they fastened a rope from some extra clothes and, timing the guard’s passes, lowered themselves to the ground. The men went down in groups of two. Augarten watched as the two Canadian pilots lowered themselves down and ran across a street adjoining the stable. Augarten and Gordon went next. After sliding down to the ground, the two made their way across the street and into the woods. They hiked for a while, before running into a Frenchman who gave them some civilian clothes. But the two soon realized that the woods were slowing them down, and decided to try their luck on the roads instead. German tanks and trucks and refugees escaping the fighting choked the roads. Augarten and Gordon walked with the refugees, using them as cover. Suddenly, Augarten heard a shout. "Halt!" He turned and saw two German SS officers motioning for him and Gordon to come over. Wearing French civilian clothing and carrying their uniforms in bundles under their arms, Augarten and Gordon walked over to the Germans. Augarten tried to remain calm, but he was gripped with fear. The SS officers began asking the men questions in German. Augarten responded in his broken French. Luckily, the Germans knew even less French than Augarten, and didn’t realize the American barely spoke the language. The officers motioned for the two men to continue on their way. The road became more and more clogged with Germans. Augarten and Gordon reluctantly decided it was too dangerous to continue walking out in the open. They found a farm and, after identifying themselves as Allied soldiers, asked if they could stay. The owner was too fearful to allow them to stay in the house. However, he agreed to let Augarten and Gordon hide in a little shack on his property, about a half-mile away from the main house. They remained there for three weeks, receiving food twice a day from the farmer’s young daughter, Madeline. Then, one day, Madeline told the two men that the Germans were growing suspicious. They were coming over to the house frequently, making it too dangerous for Augarten and Gordon to stay. The family directed the escapees to another area where some other soldiers were hiding. A few miles away, Rudy and Gordon found half-dozen black Senegalese troops in hiding. They had hooked up with members of the French underground. The group told the two that the Germans were retreating from the area. The Senegalese were thinking of more than simple escape from the retreating Germans. They were armed, and hoped to pick off some of the Germans. With Augarten and Gordon in tow, the Senegalese and their underground comrades positioned themselves along a road bounded on both sides by a ditch and a hedgerow. The men split up into two groups and hid behind the hedgerows. As dusk approached, a German soldier riding a motorcycle came speeding down the road. The men held their fire, and the motorcycle passed quickly and without incident. About five minutes later, the same motorcyclist came back from the op- opposite direction. This time, one of the men squeezed off a round. The shot missed, and the German sped off into the distance, About an hour later, Augarten heard something coming up the road. He looked in the direction of the sound, and saw a group of soldiers marching alongside a tank. In the twilight, Augarten couldn’t see the soldiers very well. All of a sudden, shots were fired from down the road toward the men and their tank. The tank stopped and the soldiers dove into the ditches sandwiched between the road and the hedgerows, only a few feet away from Augarten’s group. Augarten held his breath, straining not to make any noise. Just then, one of the soldiers who had jumped into the ditch whispered loudly, "For Christ’s sake, McCarthy, get off my foot!" Augarten couldn’t believe his luck. "Are you Americans?" he asked the men. "Yes. Who are you?" came the reply. The soldiers took Augarten and the others to the company commander, who arranged for the group to be driven to Allied lines, about fifteen miles away. The American’s two-month adventure through German-occupied France had finally come to an end. Considering the ordeal Augarten had just been through, the army felt it appropriate to send him home instead of back into combat. But Augarten refused. He had pulled a lot of strings to get into the fighting in the first place, and had flown only ten missions before being shot down. Augarten formally requested permission to remain in Europe with his unit, and his request was granted. He telegraphed his parents to tell them he had survived, and went back to flying. During the remainder of his tour, Augarten flew over ninety missions. One of these stood out from the rest. During that flight, Rudy engaged several Messerschmitts, shooting down two. That feat earned him the Distinguished Flying Cross.

After the war, the twenty-three-year-old Augarten returned to the States and began his university studies. He was studying International Relations at Harvard, as events were heating up in Palestine in early 1948. On the suggestion of a friend, Augarten attended a lecture at the Harvard Library given by a young Palestinian diplomat, who turned out to be Abba Eban, then a diplomat and representative of the new State of Israel and, much later, Israel’s foreign minister. After the lecture, Augarten told a friend active in a local Zionist group that he wanted to do something for his fellow Jews in Palestine. The friend gave him the address of someone to see in New York. On his spring vacation, Augarten visited the offices of Land and Labor for Palestine, a front organization recruiting volunteers to fight for Israel, in Manhattan and told them about his background. At that time, the Israelis had been able to recruit only a handful of pilots, and they were very impressed with his war record. They asked if he could go to Palestine immediately. Augarten agreed, and went to tell his parents about his decision. Augarten’s parents were bitterly opposed to his returning to flying. The strain of having a son missing in action for more than two months had taken its toll. They were not prepared for Augarten to return to the dangers of combat. Deferring to his parents, Augarten decided not to do anything immediately. He returned to his studies at Harvard. As reports of the fighting in Palestine got worse, however, Augarten could not stay away any longer. He got back in touch with Land and Labor and arranged to fly out as soon as exams were over. To avoid another confrontation with his parents, he sent them a letter, timed to arrive after his departure. Rudy arrived in Israel shortly before the second truce, after receiving his Messerschmitt training in Czechoslovakia.

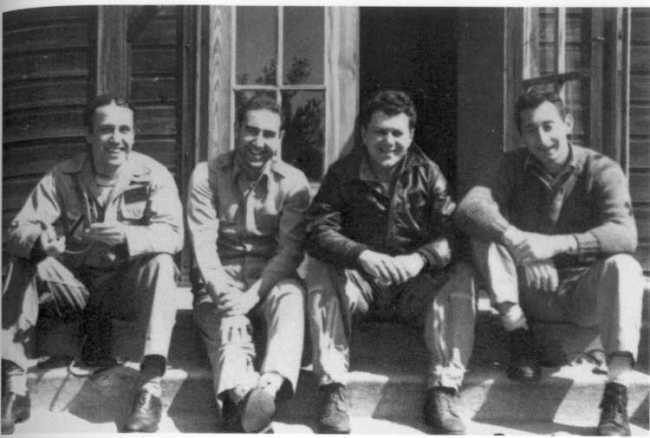

Training in Czechoslovakia on the Me-109. Left to right: Chris Magee, George Lichter, unidentified and Rudy Augarten.

A few words needs to be said about the main fighter plane of the Sherut Avir – Air Service, as the Israeli Air force was called in the beginning of the War for Independence. I personally consider the fact that this plane was Israel’s first fighter one of the biggest ironies of history. The correct name of this plane is Avia S-199. After World War 2 a large number of Messerschmitt BF-109G airframes was left at the Czechoslovakian Avia factory, which was building planes for the Germans during the occupation. But the Daimler-Benz DB-605 engines used on the real Messerschmitts were not available. However, Junkers Jumo-211 engines were. These engines, along with wide-blade propellers, were used on German Heinkel He-111 and Junkers Ju-88 bombers during the war and were ill-suited for a fighter aircraft. Nevertheless, these Jumo-211 engines were fitted to the Me-109 airframes. This resulted in the plane that was extremely cheap to produce, but with such flight characteristics, that the pilots who flew it for Israel nicknamed it "Nazi Revenge". The plane was called Me-109 out of habit, or, maybe, out of wishful thinking. Unfortunately, it was very far from the vaunted Messerschmitt flown by many German aces during World War 2. The engine switch caused the plane to pull left on take-off and right on landing, sometimes so violently that the Me-109 actually flipped over. Another problem was that its two nose machine guns designed to shoot through the propeller disk had a tendency to go out of sync, causing several pilots to literally shoot themselves down by shooting off their own propellers. In addition to this, the 20 mm cannon that was firing through the propeller hub in the original Me-109 had to be removed. To increase the firepower two 20 mm cannons were added in the underwing pods, causing additional drag and weight increase. Nevertheless, the Israelis were happy to get any fighters, and even with all these problems, the Me-109 was still fighter plane enough for the veteran pilots of the new Israeli Air Force to hold their own against the superior Spitfires flown by the Egyptians.

Israel was in short supply of almost everything, and with less than ten serviceable fighter planes in the entire country, the 101st, the only fighter squadron in the country, was particularly afflicted. It didn’t have enough planes for the two dozen pilots who were capable of flying them, and there was competition for each flight. On October 16, 1948, one day into the first major Israeli offensive against the Egyptians called Operation Yoav, Augarten’s turn had finally arrived. Egypt’s air base at El Arish had been one of the sites of the previous day’s raid by Israel’s only fighter squadron, the 101st. Augarten was on a photo-reconnaissance mission to determine what targets the air force had destroyed, and what it needed to finish off. Although his assignment was simple, he was happy for the chance to be flying at all. Rudy flew southwest toward the coast. Suddenly, in the distance, he spotted two Spitfires flying in formation. Augarten could tell by their shape that they were not Me-109s, like the plane he was flying. Rudy was too far away to make out their markings, but it didn’t matter. Even though the Israeli Air Force had several Spitfires in its arsenal, he knew immediately that the two Spits were Egyptian. Because mechanical problems and fuel shortages limited the Israeli Air Force to only a few planes in the air at any one time, the pilots were always confident when they saw another plane that it was not one of their own. Augarten carefully got into position behind the two Egyptians, hoping they wouldn’t detect his approach. Just then, fellow 101 pilot Leon Frankel, who was patrolling in the area, saw Augarten beginning to engage the Spits. Trying to come to Augarten’s aid, Frankel rolled his plane over and dove toward the combatants. But before he reached the scene, Augarten lined up one of the Spits in his gunsight, and fired a burst from the Me-109’s two 7.92 millimeter machine guns. Pieces of the Spitfire flew off as the bullets pierced its thin aluminum body. The Egyptian plane plummeted toward Israeli lines, leaving a trail of black smoke. The other Spit fled the battle scene. With no other enemy planes in sight, Frankel and Augarten fell into formation for the trip back to the base. A few days later, Augarten got a treat few fighter pilots ever receive. An army unit took him by jeep to see firsthand the wreckage of the plane he had downed. Smiling broadly, he posed for a photograph in front of what remained of the Spit. With that victory, Augarten had experienced the Czech version of the Me-109 at its best.

Rudy in front of the Egyptian Spitfire wreckage.

His victory at the beginning of Operation Yoav was his first as a pilot in the Israeli Air Force, but it would not be his last. The next day after the capture of Beersheba, Rudy Augarten was again in the air over the Negev. This time, Augarten was in one of the squadron’s new Spitfires. He was not alone on this flight. Canadian Jack Doyle flew the other Spit at Augarten’s side. As the two patrolled, they spotted four Egyptian Spitfires. Veteran pilots, Doyle and Augarten turned to come out of the sun at the enemy planes. They each picked a target, coming in with their guns blazing. Augarten recorded his second kill of the war, Doyle his first. The two pilots also damaged the other two Egyptian planes before returning home.

On November 11, Rudy Augarten left Kastina for a two-plane patrol near Egypt’s El Arish air base. Augarten’s wingman, a South African named Boris Senior, noticed an Egyptian Dakota (the bomber conversion of the famous C-47 Skytrain) lining up to land. He dove down to attack. "What are you doing? This is a truce," Augarten radioed to Senior. But by then it was too late, Senior had already fired on the Egyptian. The Dakota kept flying, though, and it was clear that Senior had missed. With his wingman having already fired his guns, Augarten felt the fallout would be no greater if the Dakota was brought down. He maneuvered behind the Dakota and fired. His bullets found their mark, and the Egyptian plane crashed just before the airfield. Rudy Augarten was particularly adept at this, as his performance in the first four days of Operation Horev showed. On December 22, he climbed into a Spitfire in response to a report of Egyptian planes in the area, and damaged a Macchi that was about to land at the El Arish air- field. Two days later, he flew a P-51 Mustang on a fighter patrol. Later that same day, he escorted a bomber on an attack on the El Arish airfield, this time flying an Me-109. The next day, he was back in the Spitfire for a photo-reconnaissance mission over Egyptian positions. During the course of the war, he would shoot down four Egyptian planes, a total matched only by Jack Doyle. Augarten, who had flown a P-47 Thunderbolt during World War II, made his four kills from an Me-109, a P-51 Mustang and twice from a Spitfire. It was a remarkable display of flying skill.

After the War for Independence many volunteers stayed on for at least a few months to help train young Israelis to fill the void created by the departing volunteers. This was particularly the case in the air force. In the 101 Squadron, Rudy Augarten and some other pilots remained in Israel to train the first class of Israeli fighter pilots. Augarten then returned to his studies at Harvard to complete his degree. He then came back to Israel, where he served for two years as the commander of the air base at Ramat David. When he resigned from the air force, he did so with the rank of lieutenant colonel.

[…] (Click here to read the story.) […]

Pingback by Significant dates in May « Conservative Liberal | May 21, 2008 |

I remember Rudy very well. He was part of our study group at Drexel Inst. of Technology (now Drexel University) in the late 50’s. Yet the write up does not mention he went to Drexel, only Harvard. After returning to the US for good, he enrolled at Drexel as a mechanical engineering student. Except for Rudy, all of us were in our twenties, too young to have fought in WW II. Rudy admitted that he was 39. All of us admired Rudy and were entranced by his war stories from both Israel and Europe.

CAN SOMEONE PLEASE TELL ME WHAT HAPPENED TO RUDY COMING BACK FROM ISRAEL.

DID HE GET MARRIED? IS HE STILL ALIVE?

Rudy Augarten married, had a son and belonged to Temple Beth Israel of Pomona, California. He passed away some years ago.

Rudy died many years ago now. He’s my step grandfather. He marrried my very sweet grandmother later in life and lived many happy years with her 🙂

Hello Marilyn-

I believe Rudy was my grandmother’s 2nd cousin. Do you know where his son and grandchildren are or how to contact them? Link to Laura Elise below does not work. Please post any info. Thanks.

I worked with Rudy at North American Aviation on the Apollo space program from 1964 to 1969. He worked as an industrial engineer and we had many dealings together as well as becoming good friends. The one thing he would never talk about were his war experiences. After I left North American, I entered the field of law. Some years later, Rudy showed up at my law offices in Rancho Cucamonga, the reasons I will not address here. It was a great reunion of old friends. I later learned of his fight with Leukemia and later passing. For those family survivors, you are blessed to have had him in your lives.

As a history buff I find all of this amazing. You and Augarten worked at North American on Apollo?? That puts RA on the stage for three of the defining events of the 20th century. Do you recall what roles you and he played at NA? I see he was a mechanical engineer. North American made the command module….

I just read a book called Angels in the Sky by Robert Gandt.

It’s about all the pilots who made the nation of Israel happen and quite a few excerpts are dedicated to Rudy.

What’s interesting is that I noticed that he retired in Seal Beach California which is where I now live. I wonder if any of his family is still alive? Would love to get a story in the local .paper about him